Bindwell is testing a simple idea: use AI to design smarter, more targeted pesticides built for today’s farming challenges.

Updated

January 8, 2026 6:33 PM

Researcher tending seedlings in a laboratory environment. PHOTO: FREEPIK

Bindwell, a San Francisco–based ag-tech startup using AI to design new pesticide molecules, has raised US$6 million in seed funding, co-led by General Catalyst and A Capital, with participation from SV Angel and Y Combinator founder Paul Graham. The round will help the company expand its lab in San Carlos, hire more technical talent and advance its first pesticide candidates toward validation.

Even as pesticide use has doubled over the last 30 years, farmers still lose up to 40% of global crops to pests and disease. The core issue is resistance: pests are adapting faster than the industry can update its tools. As a result, farmers often rely on larger amounts of the same outdated chemicals, even as they deliver diminishing returns.

Meanwhile, innovation in the agrochemical sector has slowed, leaving the industry struggling to keep up with rapidly evolving pests. This is the gap Bindwell is targeting. Instead of updating old chemicals, the company uses AI to find completely new compounds designed for today’s pests and farming conditions.

This vision is made even more striking by the people leading it. Bindwell was founded by 18-year-old Tyler Rose and 19-year-old Navvye Anand, who met at the Wolfram Summer Research Program in 2023. Both had deep ties to agriculture — Rose in China and Anand in India — witnessing up close how pest outbreaks and chemical dependence burdened farmers.

Filling the gap in today’s pesticide pipeline, Bindwell created an AI system that can design and evaluate new molecules long before they hit the lab. It starts with Foldwell, the company’s protein-structure model, which helps map the shapes of pest proteins so scientists know where a molecule should bind. Then comes PLAPT, which can scan through every known synthesized compound in just a few hours to see which ones might actually work. For biopesticides, they use APPT, a model tuned to spot protein-to-protein interactions and shown to outperform existing tools on industry benchmarks.

Bindwell isn’t selling AI tools. Instead, the company develops the molecules itself and licenses them to major agrochemical players. Owning the full discovery process lets the team bake in safety, selectivity and environmental considerations from day one. It also allows Bindwell to plug directly into the pipelines that produce commercial pesticides — just with a fundamentally different engine powering the science.

At present, the team is now testing its first AI-generated candidates in its San Carlos lab and is in early talks with established pesticide manufacturers about potential licensing deals. For Rose and Anand, the long-term vision is simple: create pest control that works without repeating the mistakes of the last half-century. As they put it, the goal is not to escalate chemical use but to design molecules that are more precise, less harmful and resilient against resistance from the start.

Keep Reading

How a Korean biotech startup is using AI to move drug discovery from trial-and-error to precision design

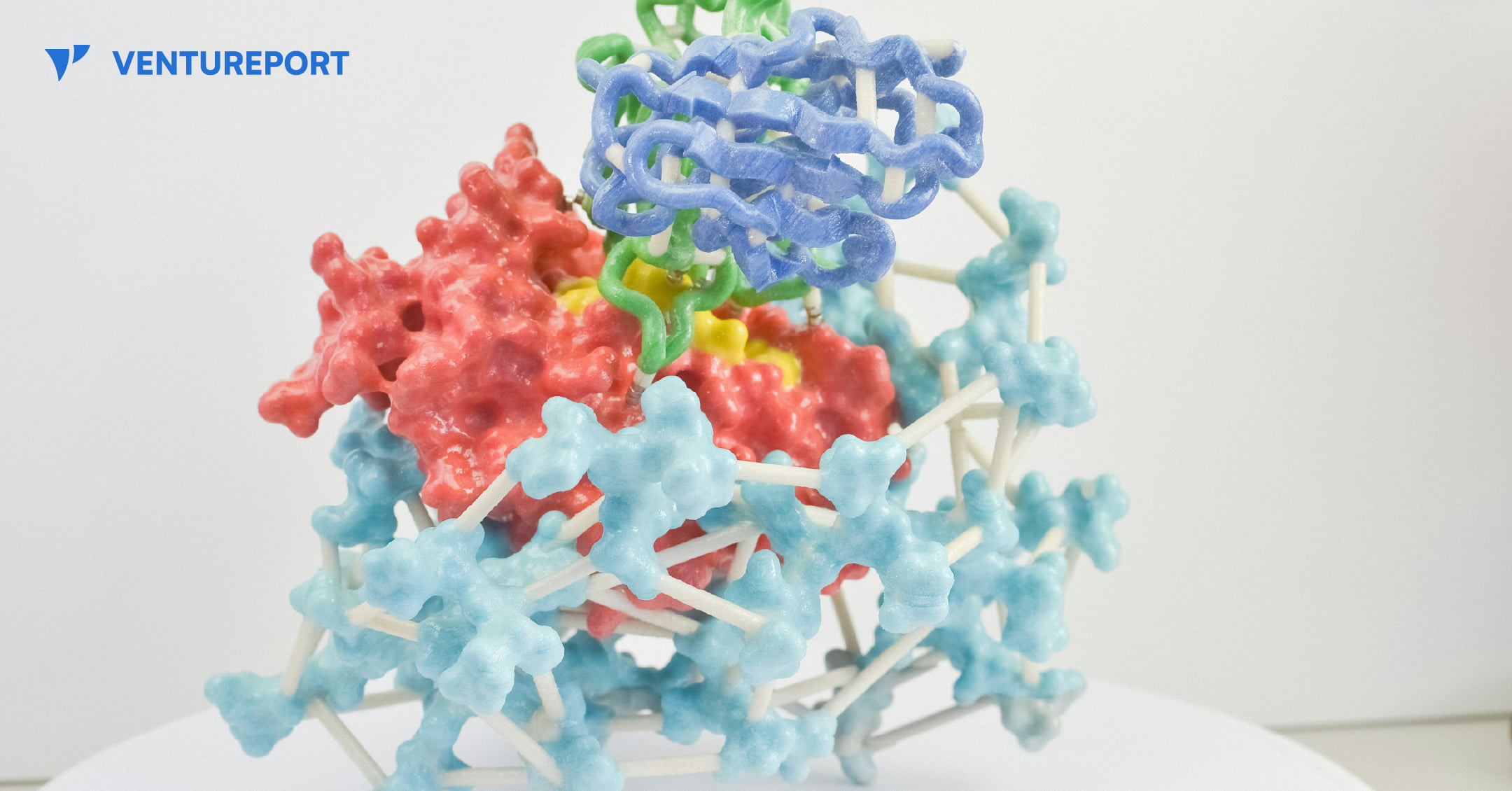

A close up of a protein structure model. PHOTO: UNSPLASH

For decades, drug discovery has relied on trial and error, with scientists testing thousands of molecules to find one that works. Galux, a South Korean biotech startup, is changing that by using AI to design proteins from scratch. This method, called “de novo” design, makes it possible to build precise new therapies instead of searching through existing ones.

The company recently announced a US$29 million Series B funding round, bringing its total capital to US$47 million.This significant investment attracted a substantial roster of institutional backers, including the Korea Development Bank (KDB), Yuanta Investment, SL Investment and NCORE Ventures. These firms joined existing investors such as InterVest, DAYLI Partners and PATHWAY Investment, as well as new participants including SneakPeek Investments, Korea Investment & Securities and Mirae Asset Securities.

At the core of the company’s work is a platform called GaluxDesign. Unlike many AI tools that only predict how existing proteins fold, this system uses deep learning and physics to create entirely new therapeutic antibodies. This “from scratch” approach lets the team go after so-called “undruggable” proteins. These are targets that traditional small-molecule drugs can’t reach because they lack clear binding pockets. By designing proteins to fit these complex shapes, Galux aims to unlock treatments that have stayed out of reach for decades. And that’s exactly why investors are paying attention.

The pharmaceutical industry is actively looking for faster and more efficient ways to develop new drugs, and Galux is built for exactly that. The company connects its AI platform directly to its own wet lab, where designs can be tested in real time. Each result feeds straight back into the system, sharpening the next round of models. This continuous loop speeds up discovery and improves precision at every step. It’s also why partners like Celltrion, LG Chem and Boehringer Ingelheim are already working with Galux.

Galux is no longer just trying to make drugs that stick to a target. The company now wants its AI to design medicines that actually work in the body and can be made at scale. In simple terms, a drug has to do more than bind to a disease—it must be stable, safe and strong enough to change how the illness behaves. Galux is moving into tougher targets such as ion channels and GPCRs. These play key roles in heart function and sensory signals. Ultimately, the goal is to show that AI-driven design can turn complex biology into real treatments. And instead of hunting blindly for a solution, the team is building exactly what they need.